“Route 66 is a giant chute down which everything loose in this country is sliding into Southern California.”

Frank Lloyd Wright, American Architect, 1867-1959

In its early days, Route 66 crossed terrain still very much untamed and undeveloped. Because of this, patches of the road remained unpaved until the mid-1930s. The infamous bank robbing duo of Bonnie and Clyde--immortalized in Arthur Penn’s 1967 film--used 66 as a get-away route as they fled Joplin, Missouri, in 1933 after a shootout with police. Because it wound through largely unpopulated and inhospitable areas, Route 66 was the ideal road for outlaws, but that did not discourage the numerous adventurers who, more and more each year, took to 66 as they traveled.

Route 66 grew, in part, from a series of paths that were used long before auto clubs petitioned for their improvement, and their unification into a single road was not accomplished overnight. As both roads and roadmaps became more standardized, production of auto club guidebooks continued, offering an entirely different take on travel than the accordion-style oil company maps that were produced at the same time.

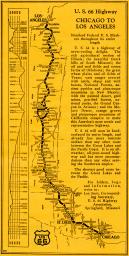

Maps, such as this one from 1933, produced at the same time by oil companies showed all potential paths available to travelers, allowing them personal choice and a sense of freedom over their own destinies, rather than a restrictive route organized by someone else.

Detail of the United States from Standard Oil Road Map Illinois

(Chicago: H. M. Gausha Company, 1933).

OML Yenson 7956.

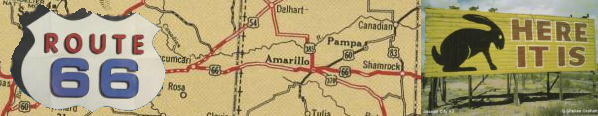

This detail of Route 66 taken from a 1930 AAA guidebook demonstrates how the book’s offerings are limited to specific routes only; there are no intersections at which a traveler could deviate from the publishing organization’s proscribed path.

AAA Western Official Tourbook; “U.S. 66 Highway.”

Washington, D.C.: American Automobile Association, 1930.

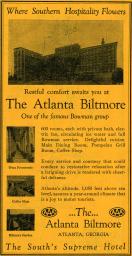

Not only the travel information differed between guidebooks and road maps. The advertising on maps targeted mobility, inexpensive pastimes, family activities, and natural attractions, while the AAA guide instead offered “The South’s Supreme Hotel” despite the fact that the guidebook did not include the South. Both the publishers and the advertisers were confident enough to include a hotel not in the part of the country the book covered because it was designed for those who would be engaging in additional travels in the future.

“The Atlanta Biltmore,” in AAA Western Official Tourbook

(Washington, D.C.: American Automobile Association, 1930).