“It winds from Chicago to LA,/ More than two thousand miles all the way./ Get your kicks on Route 66.”

Bobby Troup, “(Get Your Kicks On) Route 66,” 1946

Running more than two thousand miles from start to finish, Route 66 is a traveler’s dream. Each end is in a major city, filled with art, music, theater, and excellent cuisine, each with its own distinctive culture. Along the way, landmarks, both natural and constructed, have always been a huge draw for travelers. Diners, distinctive hotels, and stores all compete for attention with such magnificent natural sites as the Grand Canyon and the Petrified Forest. Many maps were drafted to include such locations, so travelers would be sure to get a look at everything deemed “worthwhile” along their path.

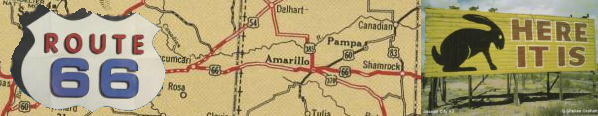

During the height of Route 66’s popularity, business-owners and map-makers alike used the road’s cultural caché to construct and identity for the road. Significant language and images mythologized this path between Chicago and Los Angeles.

Many maps were produced with the intention to not only to guide travelers, but to advertise the landmarks along Route 66, many of which were designed as self-conscious marketing tools, like the Jackrabbit Trading Post near Joseph City, Arizona, whose signs dot great stretches of the road. Another attraction that remains popular today is the Blue Whale Swimming Hole in Catoosa, Oklahoma.

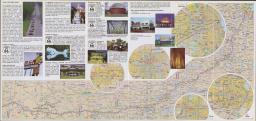

Route 66; Oceanside, CA: Global Graphics, 2002. OML Yenson 8850.

This map is worthy of note because of the way that each side of the cover says something quite different about Route 66. When this booklet style map is folded to most resemble a standard roadmap, the front announces that Route 66 is the “Grand Canyon Route” (despite the fact that the Grand Canyon is not actually right along the road) and that it runs “Across the Scenic West.” The back cover, however, refers to the road as “The Will Rogers Highway,” reminiscent of a time when highways were named rather than numbered, invoking a nostalgic feeling in the viewer and alluding toward a constructed history that reaches far beyond the commissioning of Route 66. Additionally, the back promotes that 66 is the “Shortest, Fastest, Year-Round Best.” It is only when the booklet is unfolded that one sees the rhyme in the slogans and the fact that “Main Street America,” with Chicago on one end and Los Angeles on the other, is drawn as an absolutely straight line across a far from accurate map of the United State

While many maps included the Grand Canyon or other notable sites that were close to Route 66, this map went a step farther and made Las Vegas into a must-see destination, offering a northern route between Kingman, Arizona and Barstow, California. This detour allows travelers to enjoy the glamourous goings on in Las Vegas with its casinos and resorts. Additionally, a trip to the Boulder (now Hoover) Dam and lake Mead are along the way as the traveler reconnects with Route 66.

Today, one of the most visited attractions along what remains of 66 is Meramec Cavern, Missouri, a vast system of natural caverns where Jesse James and his gang hid out in the nineteenth century. Advertisements for the Cavern are painted on barns across 14 states. Lester Dill, the man who discovered the link between Meramec Cavern and the James gang, was a pioneer in marketing. In addition to painting barns, he would provide guests to the caves with “bumper signs”--forerunners to bumper stickers. Today, the cavern is well lit, well marketed, and even handicapped accessible. Had it not been located on Route 66, it likely would not have risen to the kind of prominence in the contemporary tourism industry. Another reason for the lasting success of Meremac Cavern is that it combines the allure of both the majesty of nature and the drama and intrigue of its past resident

The final page of the map includes the statement that Route 66 takes travelers through the “most...historic sections of the country,” changing the familiar narrative in which the Northeast and Virginia can claim that kind of historical primacy. This change in the historical narrative speaks to the way in which American ideals were shifting away from the old and toward the prospects of the future in the post-war age as the country shifted focus from east to west.

Drive US 66 (Oklahoma City: Southwestern Stationary & Bank Supply, ca. 1950). OML French 5833.