The Constitution of the United States, which took effect in 1789, defined how the Union would function legislatively, administratively, and judicially. It also provided some arrangements for managing interactions between the states. But, other than guaranteeing a “Republican Form of Government” to each state (art. IV, sec. 4), the Constitution did not define the nature of the states themselves. It could not do so because each state was a sovereign and autonomous polity defined by its own constitution. The U.S. Constitution necessarily reserved some governmental functions of a communal nature (money, mail, copyright, foreign relations, etc.) to the United States government, but the majority of power and administrative responsibility lay with each individual state. Emphasis was therefore placed on the Republic not as a Union but as a collection of states. The Republic could be mapped not in one image but through a sequence of images, one per state, with no indication of how they were spatially related to each other [item 10]. Maps of individual states, each made for the state’s own residents, were as common as maps of the whole Union. Some were published within histories and other accounts of particular state [item 14]. Others were wall maps intended for the same kinds of walls—in school rooms, public buildings, and private homes—as were maps of the United States [items 11-12]. Furthermore, the localism promoted by state sovereignty extended to maps of counties within the states [item 13].

This wall hanging, probably intended to be displayed in school rooms, exemplifies the distinct political identities of each state within the larger entity of the Republic. It displays the complete text of the U.S. Constitution, complete with its first twelve amendments. Around the edge are brief descriptions of the states; each gives a summary history of the state and identifies its territorial character with an outline map. This assembly of state icons maps the Republic in precisely the same manner as an array of state seals (see item 9) or a pocketful of the “states’ quarters” currently being issued by the U.S. Mint. William Bicknell taught school in the Hartford, Maine school district for 55 years. He wrote extensively on a variety of political topics, supporting women’s suffrage and opposing the death penalty. Printed locally, his wall hanging was also most likely exhibited locally.

William Bicknell, Jr. (American, ca. 1804-1887)

The Constitution of the United States, with a Summary View of Each State in the Union

Letterpress and wood engravings transferred to lithograph, hand-colored, 76.5cm x 53.0cm

Hartford, ME, [1834]

Osher Collection

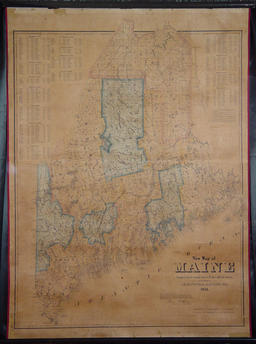

In the decade after the Constitution was ratified and took effect, the governments or citizens of several states began to produce wall maps of their territories intended to affirm publicly their political independence. Thus, William Blodget published his map of Connecticut in 1792, Reading Howell his of Pennsylvania in 1792, Dennis Griffith his of Maryland in 1795, James Whitelaw his of Vermont in 1796, and so on. It must be remembered that these wall maps were sold and displayed within the states they represented, and so defined a local sense of identity and belonging. Such mapping efforts in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts were complicated both by the geographical division of the state into Massachusetts per se and the District of Maine and by the inadequate skills of John Norman who engraved the first maps prepared by Osgood Carleton (printed in 1798). The map on display here is the second map of Maine, engraved by Callender and Hill.

Osgood Carleton (American, 1742-1816)

Map of the District of Maine Massachusetts

Engraving, sectioned on linen, 135.0cm x 92.5cm

Boston: B. & J. Loring, 1802

Fleet Bank Collection

Wall maps of the District of Maine by Osgood Carleton (see item 11) and Moses Greenleaf depicted the territory as a self-contained entity and so encouraged the idea that Maine should properly comprise a state in its own right. Maine eventually achieved independence from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in 1820 as part of the Congressional compromise which required the creation of a non-slave state to balance the newly created Missouri, in which slavery was permitted. Thereafter, large maps of the state of Maine continued to be published. By the end of the nineteenth century, state atlases were produced as well. Like his predecessors, John Mansfield compiled his 1855 map of the state from surveys housed in the official archives (as attested by a certificate from the state land agent). He rounded out the map with a tabular summary of the 1850 census, listing the population and taxable valuation of each town in the state, by county. Mansfield published the map in Bangor and, judging from the very few copies that survive today, it was not sold far beyond that very local market.

John Brainard Mansfield (American, 1826-1888)

New Map of Maine

Lithograph, sectioned on linen, 111.0cm x 86.0cm

Bangor, ME 1855

Osher Collection

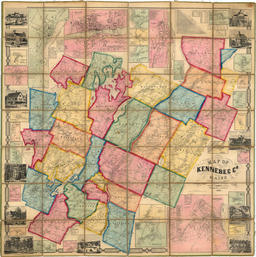

The localist impulse within U.S. life is perhaps best exemplified by the wall maps and atlases of counties which began to be published in the 1850s. John Chace, a Philadelphia publisher, organized the publication of several maps of Maine counties, such as this one of Kennebec County. The map’s dual imprint refers to the manner in which the map was prepared and printed in Philadelphia but was sold only to the local market in and around Augusta, Maine. This is an exceptionally fine example of a nineteenth-century wall map. Its coat of varnish remains clear so that, if exposed to candle- and gas-light, the map would still exhibit an especially pleasing luster. The other wall maps in this exhibition which were once varnished (items 8-11) would have been as bright and as colorful as this when originally made.

John Chace, Jr. (American, fl. 1854-1860)

Map of Kennebec Co. Maine

Engraving transferred to lithograph,

hand-colored, 142.5cm x 144.5cm

Philadelphia and Augusta, ME, 1856

OML Collections

The newly independent states were not only depicted in large wall maps but in small maps as well. These small maps were part of historical accounts which constructed identities for each state. Thus, Jeremy Belknap mapped New Hampshire in volume 2 (1791) of his three-volume history and geographical account of that state (published 1784-1792). Similar maps and books were also used to create identities for potential states. John Filson, for example, mapped in 1784 as part of his book advocating statehood for that territory (granted in 1792). Osgood Carleton, also known for his large wall maps of the state (see item 11), provided the map of Maine for James Sullivan’s 1795 history of the district. In narrating Maine’s history, Sullivan focused on its legacy of war, first with Native Americans and then the British. Note, in particular, the large inset map of coastal Maine, the region “most famous for being harassed by the Indians.”

Osgood Carleton (American, 1742-1816)

A Map of those parts of the Country most famous for being harrased by the Indians

Engraving, 52.0cm x 42.0cm

In: James Sullivan, The History of the District of Maine (Boston: I. Thomas and E. T. Andrews, 1795), opp. title page

Osher Collection