The Declaration of Independence established the idea of the Union of the original thirteen colonies—“one People”—opposed to British tyranny. Even so, Americans in the Early Republic adapted the standard British colonial geographical image for their maps of the republic, an image which stretched only as far as the Mississippi River. This image was so well established that it persisted even after the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 extended U.S. territory across the continent to the Pacific Ocean. This geographical convention culminated in Samuel Lewis’s oversized wall map of 1816 [item 6]. General interest in the lands West of the Mississippi was finally aroused by the War of 1812. Americans began to treat the West as a place both of infinite promise and of the fulfillment of the political aspirations embodied in the Declaration of Independence, ideals which would later be codified in the concept of “Manifest Destiny.” Just a few months after Lewis’s map appeared, John Melish published the first map to show the whole sweep of the country, from the Atlantic to the Pacific [item 7]. Melish’s geographical image quickly became the new standard for representing the whole country. Later wall maps, produced for decorative as well as functional purposes, made explicit the connections: first, between the Declaration of Independence and the Republic, and second, between the Republic and Manifest Destiny [items 8-9].

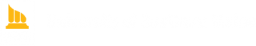

The original cartographic image of the United States—which depicted the country as far west as its original Western boundary along the Mississippi River—persisted even after that boundary was suddenly shifted all the way to the Pacific Ocean by the Louisiana Purchase (1803). This does not mean that these maps lacked a spirit of expansion and growth. Samuel Lewis’s wall map of 1816 clearly delineates the inexorable Westward movement of the frontier of Euro-American settlement. In Ohio, for example, the organized counties gave way to a wide territory emptied of Native Americans, who had been pushed to the West of the “Indian Line” and the army posts of the Indiana Territory. In limiting the geographical frame of his map, Lewis seems to have been apprehensive about the future: because there remained so much land to be appropriated and settled within the original boundaries of the United States, further expansion into the Missouri Territory appeared to be a daunting task.

Samuel Lewis (American, ca. 1754-1822)

A New and correct Map of The United States of North America

Engraving, hand-colored,

170.0cm x 187.0cm

Philadelphia: Emmor Kimber, 1916

Osher Collection

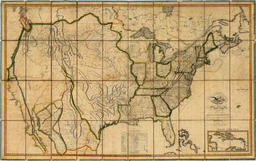

Just a few months after Samuel Lewis published his wall map of the United States, John Melish dispelled Lewis’s territorial apprehension. Melish dramatically expanded the geographical frame of the Republic. His initial concept, developed during the War of 1812, was to map the United States as far West as the Rocky Mountains. But he soon realized that it would be much better to extend the map all the way to the Pacific Ocean. As he wrote in his Geographical Description of the United States (1816): “The map so constructed, shows at a glance the whole extent of the United States territory from sea to sea; and, in tracing the probable expansion of the human race from east to west, the mind finds an agreeable resting place on its western limits.” In explaining his map’s significance, Melish foreshadowed the idea of “Manifest Destiny.” The map provided, he said, a “view of the whole [nation] as being the habitation of men among whom self-government has for the first time had a fair chance of successful experiment.” It “afford[s] ... ground for thankfulness to Divine Providence, that here at last mankind have found an asylum, where all the efforts of tyrant man to shackle his fellow will be in vain; and where every man may sit under his own vine, and under his own fig-tree, and none to make him afraid.”

John Melish (Scottish/American, 1771-1822)

Map of the United States with the contiguous British & Spanish Possessions

Engraving, hand-colored, sectioned on linen, 89.0cm x 145.5cm

Philadelphia, 1816

Osher Collection

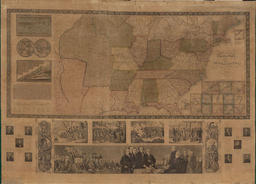

The political juxtaposition of the Republic with the Revolution and the Declaration of Independence was made explicit by culturally rich wall hangings such as this. The map (originally designed to be printed on tissue paper and folded into a pocket guide to the more populated parts of the United States) was displayed within a larger complex of images symbolizing the history and character of the Republic: (a) a rather crude rendition of John Trumbull’s 1824 painting, commissioned for the Capitol Rotunda by Congress in 1817, of the signing of the Declaration of Independence; (b-d) the text of the declaration, a facsimile of its signatures, and a key to the painting, all at left; (e-h) four images depicting iconic moments in the early history of the United States, one of the landing of the “Plymouth Pilgrims” in 1620 and three of the start and end of the Revolution; (i-j) allegories of the two great military leaders produced by America (King Philip [or Metacom], the Wampanoag sachem who fought the New England colonists in 1675-1676, and George Washington); and, (k-l) portraits of each of the Presidents in two panels. Three images of the world and its primary geographical features reinforce the common distinction between the Old World of Tyranny and Despotism and the New World of Liberty and Democracy. The overall political meaning of this wall hanging would have been quite obvious to its viewers in schools, libraries, and homes.

Phelps & Ensign (American company, fl. 1836-1850)

Phelps & Ensign's Travellers' Guide, and Map of the United States

Engraving transferred to lithograph, hand-colored, 64.0cm x 96.5cm

New York, 1841

Osher Collection

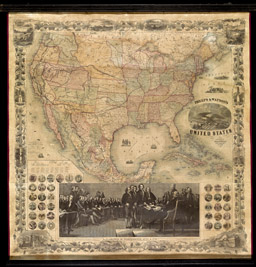

In 1845, John O’Sullivan coined “Manifest Destiny” to label the powerful beliefs and ideals which gave Americans their tremendous sense of promise. They sincerely believed that the United States should—and would—inevitably expand its territories so as to bring liberty and civilization to the Americas and beyond. Manifest Destiny drove the United States to war with Mexico in 1846-1848, to consolidate control of the far West and California, and to expand still further to the South. This 1860 wall map celebrated the Republic’s expansiveness. Among its many symbolic features are John Trumbull’s Declaration of Independence, which proclaimed the Republic’s origins in the Revolution, and the prominently delineated routes proposed for transcontinental railroads, which emphasized the consolidation of the West, now neatly divided up into administrative units. The map highlights future Southward expansion: its title proclaimed it to be a map of the United States, without acknowledging that other lands were depicted, thereby suggesting that the United States properly encompassed Mexico and the Caribbean. This suggestion is borne out by the pairing of the marginal vignettes: landscape views from the Northeast (upper-right) with those from Oregon (upper-left), and an architectural view of the U.S. Capitol (lower-right) with one of the cathedral in Mexico City (lower-left). However, this glorious image of the Republic’s unity and expansive destiny was offset by the inclusion of the seals of the individual states. These seals, depicted here on the eve of the Civil War, acknowledge the other concept of the United States as comprising sovereign states. The territorial expression of that concept is explored in the next section of this exhibition.

Phelps & Watson (American company, fl. 1860-1870)

Phelps & Watson's New Map of the United States

Steel and wood engravings transferred to lithograph, hand-colored, 94.0cm x 91.0cm

New York, 1860

Osher Collection